Climate change provided high octane fuel for Hurricane Michael

Sometimes connecting climate change to a specific weather event is difficult. With Hurricane Michael, it's not.

The science is easy: Earth's waters are getting warmer due to an increasing global temperature, and warmer waters fuel hurricanes.

Water temperatures in the far northern Gulf of Mexico were 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit higher than normal for this time of year. Instead of water temperatures being near 80, they were in the mid-80s as Michael moved over the Gulf and approached the Florida coast.

That's a huge difference. Even a small temperature bump in the ocean causes a tremendous addition of energetic heat and water vapor to a storm, meaning higher wind speeds and more storm surge. All other things being equal, a storm hovering above 85-degree water will become much stronger than a storm hovering above 80-degree water.

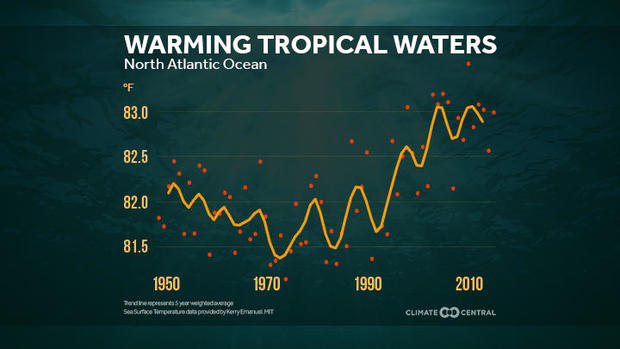

Since the mid-1900s, Tropical Atlantic water temperatures have increased by 1 to 2 degrees Fahrenheit, and more in some spots.

To climate scientists, the link between warming waters -- and a warming planet -- and greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide is as clear as day. Carbon dioxide acts like a blanket, and as more of it is produced by humans through the burning of fossil fuels, the blanket gets thicker. Since 1850, carbon dioxide concentrations have increased 30 percent.

According to Kevin Trenberth of the National Center For Atmospheric Research in Colorado, ocean heat has been accumulating due to global warming. In fact, the latest United Nations Inter Governmental Panel on Climate Change report said 93 percent of the excess heat produced by human-caused global warming is now stored in our oceans.

The water is not only warmer. It also stays warmer for longer. Water temperatures in the northern Gulf of Mexico should have cooled off more by now. They haven't.

As a result, Michael -- a powerful Category 4 storm -- shattered late-season records. According to Colorado State University hurricane expert Philip Klotzbach, Hurricane Michael is the strongest storm on record to make U.S. landfall in October. It was also the strongest landfall on record for the Florida Panhandle.

A satellite loop of Hurricane Michael shows the storm core becoming better organized and intensifying as it approached the northern Gulf Coast. That's not a common sight, especially late in the hurricane season.

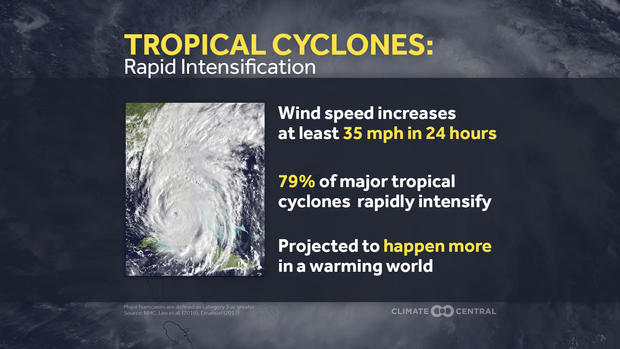

Between Monday and Wednesday, Michael's winds jumped 80 mph in 48 hours -- something called "rapid intensification." That occurs when a storm's winds increase by 35 mph in 24 hours. Michael exceeded that criteria.

Research shows that rapid intensification will become more common in the future. In a 2016 paper, leading climate scientist Kerry Emanuel of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said, "the incidence of storms that intensify rapidly just before landfall could increase substantially by the end of this century."

Just two weeks ago, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, published a study using a state-of-the-art hurricane climate model. They found that rising sea surface temperatures due to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions will likely lead to a greater number of major hurricanes in the future. That is a consistent finding in most hurricane climate research.

"The chance of a category 4 or 5 is higher now than it was in the past," said Adam Sobel, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at Columbia University. "And the likelihood for rapid intensification is increasing as well. Both of these were true for Hurricane Michael."